One evening not long after my daughter was born, I got out of the house and attended a crop—a gathering of people who work on their scrapbooks. During show and tell time, one of the veteran scrapbookers, whose name was Helen, held up a page from her album. The page featured her young daughter sneaking into the cookie jar. On her page, Helen had written out the lyrics to the children’s song, “Who Stole the Cookie from the Cookie Jar?” Accompanying the lyrics were three photographs that showed, in turn, her daughter approaching a cookie jar on the kitchen counter, reaching her hand into the jar, and, finally, extracting a cookie. Helen’s page inspired me, especially since I recently had become a parent. I thought it provided a good lesson in memorializing the type of mischief my own daughter soon would be getting into.

After the group oohed and aahed over the page, Helen dropped a bomb. She admitted that she had made the whole thing up. Her daughter did not, in fact, steal a cookie from the cookie jar, at least, not on this occasion. Helen described how she had staged each photograph, telling her daughter how to pose and then snapping the shots because she knew that they would make a memorable page in her album.

Helen’s story bothered me, and I knew that my training as an art historian was the reason. Historians are taught that it is unethical to make up events. Even when we wish that something had happened—it would clinch our argument, perhaps, or tie the chaos of the past into a neat little bow—we don’t say that it did. Yet Helen admitted to doing precisely that. And her invention was fairly egregious. Helen did not, in her scrapbook page, merely fill in details missing from her memory of the cookie jar episode. She did not enhance the episode by making it seem more exciting or dramatic. These kinds of embellishments might have been acceptable. Instead, Helen made up an event out of whole cloth and then enshrined it as history. I feared that she had broken the unwritten historian’s oath: do no harm to the past.

But here’s the thing: Helen’s page told a great story. It was the kind of story that makes the past come alive, the kind with which parents like to embarrass their children later in their lives. And she had designed the layout of the page with care, so that it had visual appeal. She even had printed the photographs in sepia tones (which, incidentally, gave them an aura of historical authenticity). I wished that I had her evident talent at putting together a scrapbook page. My other scrapbook friends also admired Helen’s work. What is more, none of them seemed bothered by the niggling detail that she had chronicled a fictional event.

The reaction of my friends, as well as my own admiration for Helen’s page, cast doubt on my initial assessment. Was Helen on to something? Does invention have a place in the chronicling of the past? These questions caused me to reevaluate what I believe about history. They led me to a group of historians whom I know quite well and who prompted me to consider whether I, too, might remake the past to my own advantage.

In one sense, most of us remake the past on a regular basis. The camera, so ubiquitous today that it often doubles as a telephone, makes everyone an historian. As we point and shoot for posterity’s sake, many of us get the niggling feeling that we never will be able to capture an event exactly as it happened or even as we remember it—we simply are unable to. And sometimes we don’t want to. Before and after we take our photographs, most of us choose to doctor them in some way. We pose them, frame then, Photoshop them, and then select the ones that will make it into the public version of our past.

I am unlikely, for example, to include in my scrapbook any pictures of my infant daughter screaming (her favorite activity the first few months of her existence). I will stick to the shots in which she sleeps and coos like an angel. The official pictorial record of my daughter’s life will, therefore, not conform to the past as I experienced it. I take history into my own hands to an even greater degree when I direct my daughter’s activities with an eye toward taking her picture. When I snap some shots of her playing with her ball, a part of me knows that she might not have played with it in just this way if I, camera in hand, had not prompted her. Hold it up! Now throw it—no, not over there, toward the camera! But my photographs—the historical record—will give the illusion that no such intervention influenced her play. I do not feel badly about directing the course of events in this way because, as a student of the visual arts, I know that photographs never mirror reality, no matter how hard we try to make them do so. It isn’t in the nature of the medium.

When I write about the visual arts, however—when I put on my “serious historian” hat and produce an art historical text—I like to think that I can get my mirror accurately to reflect their historical context. But here, too, invention not so subtly creeps in. The past does not present itself whole for our inspection. As historians, we have to use our techniques, our skills, and our judgment to piece together and make sense of its fragments. At the same time, we usually are trying very hard to convince an audience that we have interpreted these fragments correctly. Every time an historian does this—every time she speculates, fills in gaps, or marshals evidence to support an argument—she noodles around with “what really happened.” Some philosophers of history would go further and say that the past—even last year, even yesterday—exists only in our invention of it in the written word.

When I was in graduate school, I used to play a little game that bears out this point. While working on my dissertation, I would stop and ask myself whether I could imagine making an entirely different argument, using the same data I had at hand. Essentially, I staged mental historical debates. Somewhat surprisingly (given my wholehearted investment in the thesis of my dissertation), I usually could imagine arguing the opposite point of view and arguing it convincingly. Each interpretation of the evidence, I realized, would make the past anew; it would reinvent it.

Of course, there still would seem to be a big difference between inventing the past through arguments and reconstructions and inventing the past through making things up. Perhaps we cannot get at “what really happened.” Perhaps we have to help the past along in all kinds of ways. But we do not outright fake the past, as my friend Helen did. Every serious historian I know would frown upon the wholesale invention of a fact or an event. It simply isn’t done.

But it has been done before and by historians I admire. They just don’t happen to be living historians. They themselves are part of history, and they remind us that the taboo against invention is largely a modern one, based upon what we think history is and what it does. I know full well that if I had fabricated the events I chronicled in my doctoral dissertation, I would not have earned my degree. But if I had lived a mere seven hundred years ago, I would have. In the Middle Ages—the very period on which I wrote my dissertation—the crafting of history followed different rules than it does today. It was closer in spirit to Helen’s cookie jar page.

When I wrote academic art history articles, I often felt that I was sending them into the void. They looked good on my c.v., but I did not know who, if anyone, read them. Nor did I write them for the benefit of a particular person or group. I wrote history that interested me but that remained, in the final analysis, disinterested. This is the kind of history my training taught me to write. A medieval chronicle, by contrast, often was written within and for a community—a family, a society, or a nascent country. Within this community, it frequently was intended for a specific person, often a ruler—although other people also read it—and the historian himself formed part of the same community, if not always the same social class. Medieval history did not merely or even primarily document facts. It created, cemented, and celebrated ties. Perhaps for this reason, it could be rife with invention. It resembles nothing so much as the tales told by a family gathered around the hearth on a cold winter night. And, as every family knows, many of these tales—in my day, we walked three miles each way to school, and it was uphill both ways!—must be taken with several large grains of salt.

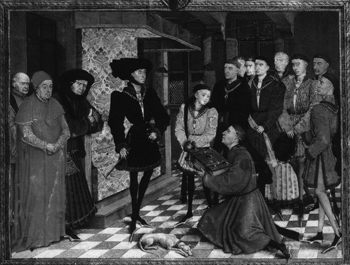

One of my favorite medieval “families” is that of Philip the Good, third Valois duke of Burgundy (1419–1467). Philip, an ambitious French prince, spent most of his career fashioning himself as the “Grand Duke of the West” and seeking the independence of the Burgundian state. His dreams of Burgundy’s future led him to the past. While not an author himself, the duke commissioned numerous histories that chronicled the origins and development of his territories. His highly ambitious claims make for enjoyable reading today.

Like many European rulers, Philip the Good was obsessed with ancestry and traced his family tree as far back as possible. One of his most illustrious histories, the Chroniques de Hainaut, gave him a Trojan pedigree. The Chroniques relates that Bavo, cousin to King Priam of Troy, set sail after the fall of the city and became the first duke of Burgundy when he founded the city of Bavais in Hainaut. With this story, Philip could compete with the French monarchy, the first to claim descent from Trojan royalty. Philip even tried to best the French by having his foundation story included in another of his chronicles, the Fleur des Histoires, a universal history that relates historical events from the creation to the year 1422. Universal histories of the Middle Ages look to God as the primary explanatory factor for historical events. The Fleur thus carried the implicit argument that the Creator himself had ordained the foundation of an independent Burgundian state.

As venerable as was the Trojan foundation legend, Philip doubtlessly would have been even more pleased to read the report of court memoirist Olivier de la Marche, who, after the duke’s death, reiterated an older claim that the Burgundian line sprang from none other than Hercules. On his way to Spain, the story went, Hercules married a Burgundian noblewoman named Alise, and their union produced the first “Roys de Bourgoingne.” With this tale, Philip was promoted to the ranks of the truly heroic, perhaps even the deified.

These competing claims—which, thankfully for the duke and his descendants, few if any contemporaries attempted to reconcile—seem to us to be bits of fantasy difficult to fathom in a serious history. But Philip the Good took his history quite seriously. He recognized that almost as much as military conquest, the right genealogy could uphold a ruler’s territorial claims. Thus he and his heirs became descendants of both the Trojan nobility and a demigod, along the way claiming other kinds of ties to such heroes as Alexander the Great, Jason the Argonaut and the Old Testament judge Gideon. With its fantastic array of forebears, Burgundian historiography is in many ways a larger-than-life celebration of Philip’s family tree—like a good scrapbook ratcheted up a few levels.

We perhaps could excuse Philip’s chroniclers at least some of their grandiosity since they wrote about distant events. They faced gaps in the historical record the size of which allowed a fair amount of speculation. But even recent events could inspire medieval historians to flights of silver-tongued fancy. A good example can be found in the Chroniques of fourteenth-century historian Jean Froissart. The Chroniques purport to give a mostly eyewitness account of events surrounding the Hundred Years War in France and England. In Froissart’s own words, he sets out to record honorable adventures and noble feats of arms “so that whoever reads or hears this work may find in it both pleasure and good example” (Froissart 1968, 3).

Froissart at first appears to be a conscientious fact checker, sometimes letting the reader in on his research process. The Chroniques’ third volume, for example, opens with Froissart’s journey to the castle of the count of Foix, Gaston Fébus, located in Béarn. Froissart traveled there to gather eyewitness testimony about the wars in the Iberian Peninsula. After his arrival, he narrates what has become one of the Chroniques’ most memorable accounts. Froissart writes that, while resident at Gaston’s court, he read aloud nightly, over a period of about twelve weeks, from his Arthurian romance, Meliador. He is self-evidently proud of the respect his performance commanded:

The count was pleased by it [Meliador], and every night after supper I used to read part of it aloud, amid complete silence, so keen was the count’s interest. When he wanted to discuss a particular point in it, he would talk to me in good French, and not in his native Gascon. (Froissart 1968, 283)

Froissart here inserts himself into the events that he chronicles. He becomes an historical player, a hero who will be remembered for his role in court pageantry as much as for his work recording other heroes’ quests.

At least one contemporary historian, however, believes Froissart’s account of this dramatic reading to be fictitious (Diller 1998). Too many inconsistencies with other historical records indicate that Froissart created it as a literary device. He also may have invented the informant with whom he reported traveling to Béarn and from whom he supposedly gleaned a good many of his facts about the region’s history.

I find it deliciously ironic that Froissart fabricated events embedded in a larger narrative of a fact-finding mission. Froissart checked his facts, but sometimes he checked them at the door. Fabricating events did not deter him from pursuing what he earnestly calls “the truth about matters” (Froissart 1968, 282). The funny thing is, I believe that Froissart did tell the truth—at least, the truth as his contemporaries would have understood it. A truthful historical account, in Froissart’s time, made events memorable; it chronicled “what could have happened” or “what should have happened” instead of the much poorer version of “what actually happened.” And as both Froissart and Philip the Good show, this version of truth frequently served a larger goal: that of locating one’s self or one’s family (however extended) in the vast web of history.

I understand this goal. I understand it because I spent five years researching my doctoral dissertation on a chronicle written and illustrated for Philip the Good. My research convinced me that the goal of medieval historians—to find themselves in the past—transcends historical time and place. As I wrote my dissertation, I myself became enamored of the duke’s vision of history. I admired his boldness in claiming pretty much whatever he chose about the past, not to mention his ability to get away with it. Even as I followed all the scholarly rules documenting his approach to history, I secretly wanted it for myself. Who does not sometimes want to rewrite events, even the small ones, in order to transform a “should have happened” into a “did happen?” Who does not wish to see herself placed amidst the pageantry of history unfurling around her?

Perhaps all historians do. Taming the past in order to tame ourselves might be the reason many of us do history in the first place—only we usually are bound by rules that do not let our desires become translated onto the page. Scrapbookers certainly want this version of history. And, not beholden to the conventions of academe, they have found a way to get it. They have tapped into the mindset of the Middle Ages—not consciously, perhaps, but in practice. My friend Helen, with her fictional cookie jar story, reminds me in many ways of a Philip the Good or a Jean Froissart. Her motivation for doing history closely mirrors their own. When she made her scrapbook page, Helen did not set out factually to document an event. Instead, she wanted to tell a story about the past. Like Philip the Good, she wanted it to be a little larger than life. Like Froissart, she wanted it to be memorable. Since so much of what happens in the past is neither of these things, Helen went and made the past her own.

I wondered if I could do the same in my own scrapbook. The stakes were not high—if I chose not to tell anyone, who would know but me?—and I would have the chance to rewrite history any way I liked. One day, I got my opportunity to find out. On one of the rare occasions my infant daughter stopped screaming and took a nap, I observed her sleeping with one arm raised over her head. I reached for my camera, for her gesture was one I habitually had made as a baby—almost. My baby book reveals that I used to sleep with my arm thrown over my eyes. I saw immediately what I could do: I could reposition my daughter’s arm so that it lay over her own eyes and take her picture. I could then make a scrapbook page that featured her photograph and my baby photograph as a charming way to affirm that our family had come full circle. It would take only a small intervention in reality to give birth to a new family legend.

The temptation was certainly there. My finger rested on the camera’s button; my daughter slept sweetly on. But I did not take the picture. The modern historian’s code, the one that discourages the outright fictionalization of the past, bound me too strongly. In a way, I wish I had been able to do it because that picture of my daughter would have made an interesting page in my scrapbook. It would have told a memorable story—just as Helen’s cookie jar story is memorable, just as Froissart’s tale of his performance at the court of Gaston de Foix is one of the most memorable in the Chroniques. But I could not, in the end, fake an event that did not happen. Despite my admiration for the historians of the Middle Ages, I am going to have to stick with a documentary approach to history, even my personal history.

My decision does not mean that I have an infallible hold on the past. Like everyone else, I direct events with my camera so that I will get a better picture; I exaggerate and embellish when I brag about my daughter. When I do so, I am aware that embellishment lies dangerously close to invention. The two exist on a sliding scale, and both betray our desire to remake the past in our own image. My identity as an historian dictates that I stay on the more “factual” end of the scale. But revisiting the medieval historians I studied all those years ago helped me to understand why Helen preferred the other, more creative, end. I cannot do that kind of history, but I am glad to see the medieval mindset alive and well in some circles today.

The next time I attend a crop, I will not be surprised if someone produces a scrapbook page like Helen’s. I will plod along making my own documentary history. And I will enjoy everyone else’s stories. I may not be able to reconcile the medieval and modern approaches to the past, but the two surely can coexist in my presence.

Lisa Deam is a writer and art historian who lives in Valparaiso, Indiana.

Works Cited

Diller, George T. “Froissart’s 1389 Travel to Béarn: A Voyage Narration to the Center of the Chroniques.” In Froissart Across the Genres. Donald Maddox and Sara Sturm-Maddox, eds. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida, 1998: 50–60.

Froissart, Jean, and John Jolliffe. Chronicles. New York: Modern Library, 1968.