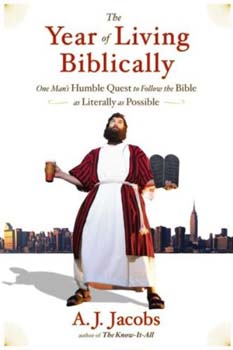

A.

J. Jacobs. The Year of Living Biblically: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow

the Bible as Literally as Possible. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2007.

A.

J. Jacobs. The Year of Living Biblically: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow

the Bible as Literally as Possible. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2007.

In The Year of Living Biblically, author A. J. Jacobs traces a year spent trying to follow every law listed in the Hebrew Bible and New Testament. Jacobs discusses a variety of reasons for undertaking such an unusual and challenging project, but he begins with this disclaimer: “I’m officially Jewish, but I’m Jewish in the same way that the Olive Garden is an Italian restaurant. Which is to say: not very” (4). Why then does he want to live a year of his life according to biblical laws large and small, rational and bizarre? He delineates several reasons for his project: 1) it makes for a good book concept (he begins with this reason because the Bible requires him to tell the truth); 2) it would be his “visa to a spiritual world;” and 3) it would be a way to explore biblical literalism (6). He also raises another, more serious reason for the project: “And most important, I now have a young son—if my lack of religion is a flaw, I don’t want to pass it on to him” (5). He later expands on this point: “I’m constantly worried about my son’s ethical education. I don’t want him to swim in this muddy soup of moral relativism. I don’t trust it. I have such a worldview, and though I have yet to commit a major felony, it seems dangerous” (39). Lastly, Jacobs discusses a possible outcome, if not goal, for the project that is especially compelling: he muses that the year-long experiment might change him in significant ways.

The actor Cary Grant has been quoted as saying, “I pretended to be somebody I wanted to be until finally I became that person. Or he became me.” Grant was referring to the difference between his extremely poor, working-class youth and the image of sophistication and wit he came to personify as a movie star. This idea of behavior determining character can be traced at least back to Aristotle’s discussion of the habituation of virtue. Today, it is manifested in the somewhat crude “fake it until you make it” mentality. Jacobs discusses the fact that such a change might happen to him as a result of his year with the Bible: “If I act faithful and God loving for several months, then maybe I’ll become faithful and God loving. If I pray every day, then maybe I’ll start to believe in the Being to whom I’m praying” (21).

This possibility is a mixed blessing for Jacobs. While he sees the potential ethical or spiritual advantages (and actual professional advantages with regard to his job as a writer), he is leery of being swept away or having any sort of deep conversion experience: “I hate losing control. I like to be in command of everything. My emotions, for instance... The problem is, a lot of religion is about surrendering control and being open to radical change. I wish I could stow my secular worldview in a locker at the Port Authority Bus Terminal and retrieve it at the end of the year” (36).

After addressing the reasons for and possible outcomes of his experiment, Jacobs faces some very practical questions: which Bible to use? What does it mean to follow the Bible literally? Should he have advisors? Should he follow both the Hebrew Bible and New Testament? For purposes of quotation, he chooses the Revised Standard Version. Jacobs also assembles an eclectic and entertaining collection of advisors from a variety of faiths. Lastly, he does decide to devote a small part of his year to the New Testament. However, he freely admits that he is more interested in the Hebrew Bible both due to his connection to it as a Jew and because it has most of the bizarre rules in it.

Jacobs quickly learns what he calls a “simple but profound lesson: When it comes to the Bible, there is always—but always—some level of interpretation, even on the most seemingly basic rules” (19). For example, the commandment against coveting: “Some interpreters say that coveting in itself isn’t forbidden. It’s not always bad to yearn. It’s coveting your neighbor’s stuff that’s forbidden... In other words, if your desire might lead you to harm your neighbor, then it’s wrong” (27). He returns to this point several times in the book, and it becomes something of a sub-motif.

Jacobs might say that there is no such thing as an archetypal fundamentalist. His honest surprise at what he discovers—that no two fundamentalist groups are the same, that there are creationists with PhDs in science, that even Amish tell jokes—never comes across as snarky or judgmental. His openness when approaching any topic—as well as his honesty when he just does not understand something—are two of the book’s strengths.

Jacobs’s willingness to play the fool, while never mocking what it is he is examining, is the source of a great deal of the book’s humor and not a little of its emotional core. Whether he’s posing on a dinosaur for a photo at the Creationist Museum (44), praying over a pigeon egg (184), or tending sheep with a Bedouin in Israel (211), Jacobs never mocks his subject. He is always willing to find the humor in an experience, but never at the expense of the person with whom he is interacting or of the particular religious tenet he is exploring. For instance, Jacobs visits Jerry Falwell’s Thomas Road Baptist Church. When sitting in on some of the seminars held prior to the service, he takes the opportunity to poke fun at himself rather than members of the church: “I wander down a flight of stairs to the singles seminar. That could be good. The woman at the singles welcoming table asks how old I am. ‘Thirty-seven,’ I say. ‘You’re right in there,’ she points. ‘It’s for singles thirty-five to fifty.’ That hurts. I am in the oldsters’ group. By the way, another fib. I am thirty-eight. Vanity” (260).

Jacobs’s journey frequently resonates with his personal life, and he does not shirk at including many of these moments. Jacobs and his wife Julie (to whom the book is dedicated) are trying to become pregnant for a second time. The author honestly—and often with sweet humor—meshes this deeply personal struggle when discussing the many sections of the Hebrew Bible dealing with fertility. Jacobs tries to comfort his wife Julie on another occasion when she has proven not to be pregnant: “There is an upside to the Bible’s infertility motif: The harder it was for a woman to get pregnant, the greater was the resulting child. Joseph. Isaac. Samuel... [I informed Julie] that if we do have another kid, he or she could be one for the ages. Which made her smile” (19–20).

Julie provides some of the book’s most humorous (and moving) sections. She is often the voice of reason when the author’s commitment to the biblical life creates painfully awkward (and quite funny) scenes with friends and family. Refraining from lying is the source of one borderline-excruciating scene. Jacobs and Julie are out for dinner with their son Jasper. They run into a school acquaintance of Julie’s who is there with her husband and child. The two families eat together. And then:

At the end of the meal, we get our check, and Julie’s friend says: “We should all get together and have a playdate sometime.” “Absolutely,” says Julie. “Uh, I don’t know,” I say. Julie’s friend laughs nervously, not sure what to make of that. Julie glares at me. “You guys seem nice,” I say. “But, I don’t really want new friends right now. So I think I’ll take a pass.” ... Julie is not glaring at me anymore. She’s too angry to look in my direction. “It’s just that I don’t have enough time to see our old friends, so I don’t want to overcommit,” I say, shrugging. Hoping to take the edge off, I add: “Just being honest.” “Well, I’d love to see you,” says Julie. “A. J. can stay at home.” Julie’s friend pushes her stroller out of [the restaurant], shooting a glance over her shoulder as she leaves.

There are other similar, if not quite as painful, moments in which Jacobs’s adherence to biblical rules butts heads with what one might term “polite society.” In some cases, Jacobs seems to relish these moments. An admitted germophobe, he delightedly puts the Bible’s many purity laws (regarding both women and men) to use as an excuse not to shake hands or hug (non-relatives) as often as possible (49, 240).

Jacobs also finds value in some of the rules that, when first taken literally, seem absurd to the non-believer. Exodus 13:9 reads, in part: “And it shall be to you as a sign on your hand and as a memorial between your eyes...” The author initially fulfills the literalist interpretation of this passage by tying a photocopy of the Ten Commandments to his wrist and to his forehead. Jacobs is surprised to find that: “It’s been startlingly effective. Just try forgetting about the word of God when it’s right in front of your eyeballs, obscuring a chunk of your vision. Sometimes I imagine the commandments sinking through my skin and going straight to my brain like some sort of holy nicotine patch... Even after taking off the string for the day (usually at about noon), I still have red indentations on my hand and head for hours afterward” (197). He does go on to try the real tradition of wrapping tefillin—the ritual of attaching two small boxes, each containing four passages from the Torah, one to the forehead and one to the left arm—and finds it moving and beautiful (199–200).

During his biblical year, Jacobs visits Israel. One of his rabbinical advisors provides him with a list of commandments that traditionally can only be fulfilled in the Holy Land—for example: tithing fruit. Jacobs buys an orange from a farmers’ market and steps outside to look for a likely recipient. He spots a tall man listening to another man reading aloud from the Bible. He approaches the listener:

“I want to give you ten percent of my fruit,” I say. “I need to give it to my fellow man on the street.” “Oh, you’re tithing?” David [the Bible reader] knew all about this and thought this was a good idea. “Problem is,” he says. “I don’t eat oranges. Give it to Lev here.” He motions at the tall guy. Lev is unsure. “Come on!” says David. “He can’t eat the orange unless you take a tenth of it.” “Fine,” says Lev. So I peel the orange and, with my index finger, dig out two sections. “Here you go!” Lev recoils. Understandably, actually. I wouldn’t take a manhandled orange slice from a stranger. “Take it!” urges David. Lev thinks about it. “How about I take the ninety percent and you take the ten percent?” He’s not kidding. I agree and keep the small chunk for myself. It’s true, what they say. Everything’s a negotiation in the Middle East. (215)

What most strikes Jacobs during the visit is that his project, even with the aid of advisors, runs contrary to a fundamental quality of the three Abrahamic faiths. He sees groups of friars, a Hasidic family with eight children, and he hears the Muslim call to prayer. He muses: “This year I’ve tried to worship alone and find meaning alone. The solitary approach has its advantages—I like trying to figure it out myself. I like reading the holy words unfiltered by layers of interpretation. But going it alone also has its limits, and big ones. I miss out on the feeling of belonging, which is a key part of religion... Maybe I have to dial back my fetishization of individualism. It’d be a good thing to do; the age of radical individualism is on the wane anyway. My guess is, the world is going the way of the Wikipedia. Everything will be collaborative. My next book will have 258 coauthors” (213–214).

The Year of Living Biblically, as with Jacobs’s previous book of immersive nonfiction (The Know-It-All: One Man’s Humble Quest to Become the Smartest Person in the World, 2004), is a remarkable mix of humor and pathos. His genuine openness to embrace behavior and concepts antithetical to his liberal, agnostic identity allows readers from across the spectrum of belief and non-belief to connect with the book and enjoy it.

While Jacobs’s book is not a work of fiction, there are many surprises in it that will not be revealed in this review. It is not too much to say that Jacobs does find himself changed when his year is over. And these changes are, he thinks, for the better: “Did the Bible make me a better person? It’s hard to say for sure, but I hope it did. A little, at least... I’m more tolerant, especially of religion, if that helps my case” (327). Jacobs best describes his year, and the book itself, with these words: “I didn’t expect to confront just how absurdly flawed I am. I didn’t expect to discover such strangeness in the Bible. And, I didn’t expect to, as the Psalmist says, take refuge in the Bible and rejoice in it” (7).

Furthermore, just as he discovered that there was more than one type of literalist, Jacobs makes another discovery that surprises him:

The year showed me beyond a doubt that everyone practices cafeteria religion. It’s not just moderates. Fundamentalists do it too. They can’t heap everything on their plate. Otherwise they’d kick women out of church for saying hello (“the women should keep silence in the churches. For they are not permitted to speak...”—1 Corinthians 14:34) and boot men out for talking about the “Tennessee Titans” (“make no mention of the names of other gods...” —Exodus 23:13). But the more important lesson was this: there’s nothing wrong with choosing. Cafeterias aren’t bad per se... The key is in choosing the right dishes. You need to pick the nurturing ones (compassion), the healthy ones (love thy neighbor), not the bitter ones. (328)

While many of the literalists Jacobs encounters during his year would disagree with him, many of us would find this observation a worthy one.

Robert D. Vega is Assistant Professor of Library Services at Valparaiso University and serves as co-editor of book reviews for First Monday, an online journal devoted to the Internet and Information Policy.