If you live beyond the Great Lakes region and know about Valparaiso University, it is likely that you are Lutheran, and even more likely that you are a college basketball fan. For many Americans, Bryce Drew’s famous last-second, game-winning shot against Old Miss in the first round of the 1998 NCAA Basketball Tournament, replayed countless times on national television whenever March Madness rolls around, put Valparaiso University squarely on the map.

But here is one thing most people—even people at Valparaiso University—do not know: as unlikely as it is that a small Lutheran university in Northwest Indiana would have a basketball program as strong as Valpo’s, it is even more unlikely it would have a museum with a collection as rich and as deep as that which resides quietly and unobtrusively at the Brauer Museum of Art.

If ever you come looking for the Brauer Museum of Art, it is not well marked. It lives in the Valparaiso University Center for the Arts,

better known in campus parlance as “the VUCA.” Signage is scarce, but landmarks

will guide you. First, get yourself to the entrance of the Chapel of the

Resurrection. It is the largest college chapel in America so you won’t miss it.

From there look north and east, to a broad brick building with an all-window

front and doorways shaped like the entrance to Agamemnon’s tomb in Mycenae,

Greece. You can google “Agamemnon’s Tomb” to get a look at that doorway.

Agamemnon’s Tomb is also called the “Treasury of Atreus.” You are looking for

the doorway to the Treasury of Valparaiso.

If ever you come looking for the Brauer Museum of Art, it is not well marked. It lives in the Valparaiso University Center for the Arts,

better known in campus parlance as “the VUCA.” Signage is scarce, but landmarks

will guide you. First, get yourself to the entrance of the Chapel of the

Resurrection. It is the largest college chapel in America so you won’t miss it.

From there look north and east, to a broad brick building with an all-window

front and doorways shaped like the entrance to Agamemnon’s tomb in Mycenae,

Greece. You can google “Agamemnon’s Tomb” to get a look at that doorway.

Agamemnon’s Tomb is also called the “Treasury of Atreus.” You are looking for

the doorway to the Treasury of Valparaiso.

Near the west entrance of the VUCA, the one nearest the chapel and also nearest the museum, you will see a large, abstract, stainless steel sculpture that rises in the shape of a V by Chicago artist Richard Hunt. Once you are in the building there is yet another Hunt sculpture, a smaller one, just opposite the entrance to the Brauer. Two more wait inside the Main Gallery, in the current exhibit entitled “New Acquisitions.” It’s crazy to think that works by Richard Hunt, the most prolific living creator of public sculpture in America, direct traffic, act as greeters, and stand like docents for the Brauer Museum of Art in Valparaiso, Indiana—but it is delightfully true.

Wikipedia has less to say about the Brauer Museum of Art than it has to say about that single shot by Bryce Drew—“the shot,” as it has come to be known—although the Brauer’s permanent collection, at last count around 4,000 pieces, includes more works by artistic “Hall of Famers,” more “All-American” artists (if there were such a thing) than will ever leave their mark on Valpo’s basketball court. The Brauer’s permanent collection, mostly American art, is remarkably comprehensive, with works by significant artists of almost every school and movement in American art from the mid-nineteenth century to the present. The museum boasts a rich assortment of religious art from around the world and includes work by internationally renowned artists such as Georgia O’Keeffe, Ansel Adams, and Andy Warhol. It also possesses a deep collection of landscapes by prominent Hudson River School painters.

Not only is the larger national narrative of American art well represented, but the regional and the local as well—the art of Chicago, of

the Indiana Dunes, of Brown County, Indiana, of the American Southwest, the

Pacific Northwest, and the midwestern heartland—it’s all there. Or so one would

think, until you see the new acquisitions, beautifully curated over the summer

to show not only how they fit into the larger story but also what unique

elements they add, what complexity and diversity they contribute that we might

not have known we were missing without them.

Not only is the larger national narrative of American art well represented, but the regional and the local as well—the art of Chicago, of

the Indiana Dunes, of Brown County, Indiana, of the American Southwest, the

Pacific Northwest, and the midwestern heartland—it’s all there. Or so one would

think, until you see the new acquisitions, beautifully curated over the summer

to show not only how they fit into the larger story but also what unique

elements they add, what complexity and diversity they contribute that we might

not have known we were missing without them.

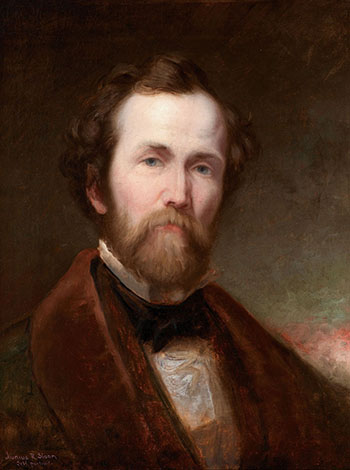

When you enter the Brauer, you come face to face with a beautiful Louis Sullivan door you can’t go through. You must turn left or right. If you go to the right, you enter the Sloan Gallery—the Brauer’s trophy case, if museums included such things. We will take a quick peek in order to meet Junius R. Sloan. There he is to the right in a charming self-portrait, and again to the right is Sloan’s portrait of his son Percy, the Brauer Museum’s first great benefactor, as just a boy.

Percy Sloan grew up in Chicago and became an art educator and collector. In 1953 he donated to Valparaiso University 276 paintings by his father and 106 paintings by other American artists, as well as an endowment to preserve and develop the collection. Percy Sloan wanted to donate his collection of his father’s work to a university that would keep it intact, conserve it well, exhibit it respectfully, and benefit from its use as a great educational resource. Percy Sloan also gave to the Brauer his father’s sketchbooks, two of which are on display, plus many letters, even ledgers. More than half a century since that original gift, the Brauer’s collection of Junius Sloan’s art has grown to 400 pieces, in a variety of media. Included among the new acquisitions are five small watercolors by Sloan, all landscapes that have a distinct Hudson River School look and feel. They came out of the blue, from two new donors.

Born on an Ohio farm in 1827, Junius Sloan began his artistic career as a self-taught itinerant portrait painter. He eventually settled in Chicago, where the market for painted portraits was sufficient for a man of his artistic skills to maintain a studio and prosper. In the Sloan Gallery you can see several of his portraits as well as portraits acquired recently by benefactors who wanted to put Sloan’s portrait painting into a broader American context.

Though Sloan made his living as a portrait painter, his passion, his purpose—what he came to describe as his religious vocation—was

landscape painting. You can usually see two of his most ambitious landscapes on

display: a salon-size oil painting entitled Kaaterskill Lakes and a smaller

landscape entitled Cool Morning on the Prairie. Kaaterskill Lakes provides a

broad panorama of the Pine Orchard, a scenic spot in the Catskills overlooking

the Hudson River in upstate New York. Thomas Cole, father of the Hudson River

School, depicted this same vista from the same spot in 1845. It is the locale

where Rip Van Winkle slept through the Revolutionary War in the Washington

Irving story. It is the same vista Natty Bumppo praised as his favorite place

on earth in a famous passage from The Pioneers, James Fenimore Cooper’s first

Leatherstocking Tale. After Cole transferred to canvas the beauty of the

Catskills that Irving and Cooper immortalized in their fiction, generations of

Americans traveled there to see it for themselves. On the left side of Sloan’s

painting a tiny image of the Catskill Mountain House appears, the first luxury

hotel in the Catskills. Long before Yellowstone or Yosemite or even Niagara

Falls became tourist destinations, this was the place where Americans

discovered leisure and learned to enjoy the natural world. For several

generations of Americans, this is where the natural world became a thing of

beauty, an object of contemplation, a source of health, relaxation, even

holiness.

Though Sloan made his living as a portrait painter, his passion, his purpose—what he came to describe as his religious vocation—was

landscape painting. You can usually see two of his most ambitious landscapes on

display: a salon-size oil painting entitled Kaaterskill Lakes and a smaller

landscape entitled Cool Morning on the Prairie. Kaaterskill Lakes provides a

broad panorama of the Pine Orchard, a scenic spot in the Catskills overlooking

the Hudson River in upstate New York. Thomas Cole, father of the Hudson River

School, depicted this same vista from the same spot in 1845. It is the locale

where Rip Van Winkle slept through the Revolutionary War in the Washington

Irving story. It is the same vista Natty Bumppo praised as his favorite place

on earth in a famous passage from The Pioneers, James Fenimore Cooper’s first

Leatherstocking Tale. After Cole transferred to canvas the beauty of the

Catskills that Irving and Cooper immortalized in their fiction, generations of

Americans traveled there to see it for themselves. On the left side of Sloan’s

painting a tiny image of the Catskill Mountain House appears, the first luxury

hotel in the Catskills. Long before Yellowstone or Yosemite or even Niagara

Falls became tourist destinations, this was the place where Americans

discovered leisure and learned to enjoy the natural world. For several

generations of Americans, this is where the natural world became a thing of

beauty, an object of contemplation, a source of health, relaxation, even

holiness.

Whereas Junius Sloan rendered Kaaterskill Lakes in a visual vocabulary that Thomas Cole invented for generations of American landscape painters, no visual vocabulary existed for Cool Morning on the Prairie before Sloan helped invent it. Cool Morning on the Prairie is an exquisite painting, for me beyond anything else Sloan painted in oil. I love how the sharp clarity of the grasses, the coneflowers, and other native prairie plants in the foreground gives way to the translucent look and feel of the low-lying fog in the middle ground, and how the split-rail fence leads our eye with those cows and that little girl to the milking shed in the distance. Sloan’s enduring importance may ultimately reside in his being one of the first artists to recognize the beauty of rural life on the American prairie and show others how to render it. This painting, and other smaller paintings of the Sloan family farm, puts Sloan at the forefront of an artistic tradition that culminates in the work of better-known American Midwest regional artists Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton, and finds its fullest literary expression in the Great Plains novels of Willa Cather.

Though Junius Sloan rightfully enjoys a place of prominence in the gallery that bears his name, nowhere else in the world do his works keep better company. Beside his portrait of his son Percy hangs a wonderful hand-colored engraving by John James Audubon entitled Grackles. Across the

gallery from Kaaterskill Lakes hangs a landscape by the acclaimed Hudson Valley

artist and teacher, Asher B. Durand. Next to Cool Morning on the Prairie hangs

a landscape by John Kensett, on the same wall with a Frederic Church and an

Alfred Bricher. These were Hudson River School painters of the first rank, as

Childe Hassam is among the very best American Impressionists. His lovely

painting of the Golden Gate hangs beside a cityscape by William Glackens, a

significant painter of the Ash Can School. Whenever Rust Red Hills by Georgia

O’Keefe is not on exhibit in Madrid or Dublin or at the Tate Modern in London,

that splendid work would appear next to the Glackens, with works of the same

era by American modernists Arthur Dove, John Marin, and now, an exquisite,

newly acquired watercolor by Charles Demuth. All this and more, in a single

small gallery. It is hard to believe you would find such riches tucked away in

Northwest Indiana.

Though Junius Sloan rightfully enjoys a place of prominence in the gallery that bears his name, nowhere else in the world do his works keep better company. Beside his portrait of his son Percy hangs a wonderful hand-colored engraving by John James Audubon entitled Grackles. Across the

gallery from Kaaterskill Lakes hangs a landscape by the acclaimed Hudson Valley

artist and teacher, Asher B. Durand. Next to Cool Morning on the Prairie hangs

a landscape by John Kensett, on the same wall with a Frederic Church and an

Alfred Bricher. These were Hudson River School painters of the first rank, as

Childe Hassam is among the very best American Impressionists. His lovely

painting of the Golden Gate hangs beside a cityscape by William Glackens, a

significant painter of the Ash Can School. Whenever Rust Red Hills by Georgia

O’Keefe is not on exhibit in Madrid or Dublin or at the Tate Modern in London,

that splendid work would appear next to the Glackens, with works of the same

era by American modernists Arthur Dove, John Marin, and now, an exquisite,

newly acquired watercolor by Charles Demuth. All this and more, in a single

small gallery. It is hard to believe you would find such riches tucked away in

Northwest Indiana.

Now let’s go left, past a small gallery just inside the main entrance where a large, beautiful blown glass bowl is spending the summer. It’s by Dale Chihuly, America’s premier sculptor of glass. Fill your eyes to brim. Then, before you enter the West Gallery, spend a moment examining a portrait of Richard Brauer, the museum’s first director, seated in the actual Treasury of Valparaiso—a vault, in fact, in the basement of the museum where most of the permanent collection spends most of its time. The vault was purchased by a local family whose generosity to the university in building the museum was such that they were awarded naming rights. Rather than put their family name on the museum, they chose to put Richard’s. Richard Brauer, choosing to have his portrait painted in the vault with the paintings he loved, was gracious acknowledgment (typical of Richard) of that gift. If you look closely at the painting, by VU alumnus Caleb Kortokrax, you can see surrounding Richard some of the museum’s most significant acquisitions. The O’Keefe is there, the Childe Hassam, Charles Burchfield’s Luminous Tree. Robert Bechtle’s 58 Rambler, a Junius Sloan, and part of a huge hyperrealist work by Joseph Raffael entitled Ch’i.

“Ch’i” is the Chinese word for an ancient Taoist concept. It

informs the practice of acupuncture as well as that of geomancy. The idea is

that a life force exists in all things and that it flows through the earth even

as it flows through our bodies. It can reside in water, in rocks, even in

paintings of water and rocks. There is, indeed, much good ch’i gathered in that

dark vault where the Raffael resides with so many companions. Oddly enough, it

is often in the summer, when so few people are around, that so much good ch’i

flows up the freight elevator, is carefully hung on the walls, and dwells in

the light.

“Ch’i” is the Chinese word for an ancient Taoist concept. It

informs the practice of acupuncture as well as that of geomancy. The idea is

that a life force exists in all things and that it flows through the earth even

as it flows through our bodies. It can reside in water, in rocks, even in

paintings of water and rocks. There is, indeed, much good ch’i gathered in that

dark vault where the Raffael resides with so many companions. Oddly enough, it

is often in the summer, when so few people are around, that so much good ch’i

flows up the freight elevator, is carefully hung on the walls, and dwells in

the light.

The first impression you are likely to have as you enter the West Gallery is what amazingly diverse and emotionally powerful art objects surround you, in just about every medium and mode of art, both two- and three-dimensional. You may be confused initially, especially if you are coming directly from the Sloan Gallery, where the work is mostly oil paintings, in mostly recognizable styles of American art, in genres easy to identify: portraits, landscapes, some urban and rural scenes, and a still life. You can understand the evolution of styles. The paintings are not difficult to read.

It’s a different story in the West Gallery. To your left hang newly acquired twentieth-century ceremonial objects from Borneo and Papua New Guinea, including an elaborately carved splashguard for a canoe, two intricately decorated Dayak shields, (one which uses human hair, the other partially constructed from a huge tortoise shell), and a carved and painted skull rack. Suddenly the context is global, non-Western, and anthropological. These objects share the wall with two works of Christian devotional art—a newly acquired body of Christ carved for a crucifix by an unnamed Spanish American artisan, and a decorated wooden crucifix carved and painted in the nineteenth century by noted Spanish santos artist José Aragon. The Aragon crucifix has long been part of the permanent collection, which from the beginning has included religious art and devotional objects from around the world. It is these objects together on the same wall that is so startling, and some version of this experience occurs often in the exhibit thanks to the skillful and strategic curating by Gregg Hertzlieb, director of the Brauer, and Gloria Ruff, associate curator and registrar. I find myself both enlightened and exhilarated by their arrangement and integration of the new acquisitions with works already in the collection. It makes the exhibition much more than the sum of its parts.

There is a great example of this on the wall to the right as you enter the West Gallery. Two batiks, products of a printing process native to Indonesia, and fashioned by a Lutheran clergyman from South India, R.

Solomon Raj, depict events from the life of Christ. These appear next to The

Birth of Christ at Bethlehem Steel, a woodcut by Northwest Indiana artist Corey

Hagelberg. These pieces are even more powerful for the company they keep. The

stylistic, cultural, and curatorial juxtapositions in the room are amazing once

your eyes and expectations adjust. And adjusting your eyes is the idea here.

There is a great example of this on the wall to the right as you enter the West Gallery. Two batiks, products of a printing process native to Indonesia, and fashioned by a Lutheran clergyman from South India, R.

Solomon Raj, depict events from the life of Christ. These appear next to The

Birth of Christ at Bethlehem Steel, a woodcut by Northwest Indiana artist Corey

Hagelberg. These pieces are even more powerful for the company they keep. The

stylistic, cultural, and curatorial juxtapositions in the room are amazing once

your eyes and expectations adjust. And adjusting your eyes is the idea here.

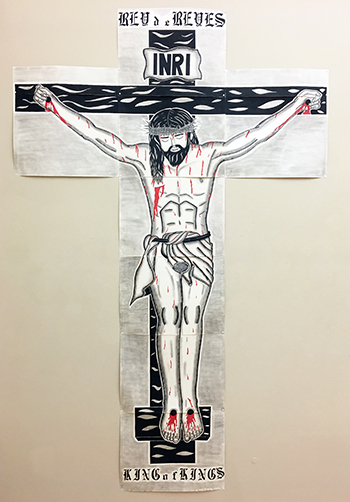

Your eyes, adjusted or not, won’t know where to rest on the wall opposite the entrance, where three large, powerful works from the permanent collection frame the new acquisition Cotton Eater II, a large color woodcut print by contemporary bi-racial artist Allison Saar. In Cotton Eater II, Saar has depicted an African American woman putting tufts of cotton into her mouth. She stands barefoot in a transparent shift, her eyes empty and white, both haunted and haunting. Her swollen abdomen suggests she is pregnant, or

starving, maybe both. To the left of Cotton Eater II is displayed Crucifixion,

a huge crucifix drawn upon panels of paper by Chicago-area outsider artist Raul

Maldonado and attached with thumbtacks in the wall. Maldonado grafts the very

bold, graphic, decorative style characteristic of Chicano tattoo and graffiti

artists upon the santos tradition of the Aragon crucifix around the corner.

Your eyes, adjusted or not, won’t know where to rest on the wall opposite the entrance, where three large, powerful works from the permanent collection frame the new acquisition Cotton Eater II, a large color woodcut print by contemporary bi-racial artist Allison Saar. In Cotton Eater II, Saar has depicted an African American woman putting tufts of cotton into her mouth. She stands barefoot in a transparent shift, her eyes empty and white, both haunted and haunting. Her swollen abdomen suggests she is pregnant, or

starving, maybe both. To the left of Cotton Eater II is displayed Crucifixion,

a huge crucifix drawn upon panels of paper by Chicago-area outsider artist Raul

Maldonado and attached with thumbtacks in the wall. Maldonado grafts the very

bold, graphic, decorative style characteristic of Chicano tattoo and graffiti

artists upon the santos tradition of the Aragon crucifix around the corner.

To the right of Cotton Eater II hang two powerful works from the permanent collection by Jewish American artists Leon Golub and Leonard Baskin. The Baskin piece serves as a great bookend opposite the Maldonado, a large woodcut print from his Holocaust Series, where a huge man stands naked and bent before us, his suffering as deeply inscribed in his flesh as in the Yiddish inscription that accompanies the image. At the bottom of the print,

Baskin translates the Yiddish into English: We Lie Here Dead and His Godly Name

Grows Greater and Holier. Here I find the curating most inspired, to place on

either side of Saar’s poor cotton eater Maldonado’s image of Christ the King

crucified and Baskin’s Holocaust victim. Additionally, linguistic and graphic

dimensions link the works. Baskin’s image is inscribed in two languages,

Yiddish and English; Maldonado’s in three: Latin, Spanish, and English. Even

the script Baskin writes in and the street font Maldonaldo imitates have

expressive power.

To the right of Cotton Eater II hang two powerful works from the permanent collection by Jewish American artists Leon Golub and Leonard Baskin. The Baskin piece serves as a great bookend opposite the Maldonado, a large woodcut print from his Holocaust Series, where a huge man stands naked and bent before us, his suffering as deeply inscribed in his flesh as in the Yiddish inscription that accompanies the image. At the bottom of the print,

Baskin translates the Yiddish into English: We Lie Here Dead and His Godly Name

Grows Greater and Holier. Here I find the curating most inspired, to place on

either side of Saar’s poor cotton eater Maldonado’s image of Christ the King

crucified and Baskin’s Holocaust victim. Additionally, linguistic and graphic

dimensions link the works. Baskin’s image is inscribed in two languages,

Yiddish and English; Maldonado’s in three: Latin, Spanish, and English. Even

the script Baskin writes in and the street font Maldonaldo imitates have

expressive power.

If the arrangement of this part of the gallery doesn’t sound divinely inspired enough, the curators have also placed between Cotton Eater II and the Baskin woodcut a painting by Chicago-born Leon Golub, a member of the Monster Roster group of Chicago artists who gained international acclaim for his politically engaged art. In this painting, entitled Niobid, a single male figure, done in the artist’s highly expressive gestural style, points directly to Cotton Eater II. To my mind, a new acquisition could not be more warmly or wisely welcomed into the family than the curators enable these artworks from the permanent collection to do. It is a classic form of Brauer Museum hospitality enacted on the walls.

If the arrangement of this part of the gallery doesn’t sound divinely inspired enough, the curators have also placed between Cotton Eater II and the Baskin woodcut a painting by Chicago-born Leon Golub, a member of the Monster Roster group of Chicago artists who gained international acclaim for his politically engaged art. In this painting, entitled Niobid, a single male figure, done in the artist’s highly expressive gestural style, points directly to Cotton Eater II. To my mind, a new acquisition could not be more warmly or wisely welcomed into the family than the curators enable these artworks from the permanent collection to do. It is a classic form of Brauer Museum hospitality enacted on the walls.

Given everything on the walls in this room, it would be easy to walk quickly by the display cases that exhibit several works of pottery. I know because I did. But I jotted down the names of the potters—Maria Martinez, Lorencito Pino, Dylene Victorno, and Lucy Lewis—and went on the internet to find out what I missed. These women are considered among the very best in their craft. One of them, Martinez, of the Ildefonso Pueblo in New Mexico, gained international acclaim for her black ware pottery, an indigenous art form that might have perished but for her re-discovery and rejuvenation of it. The forms have a beauty and near perfection that mark each of the pieces as expertly handmade. The decoration is abstract, sometimes biomorphic, other times geometrical, always a pleasure to the eye and something to think about in relation to other forms of abstract expression in the galleries. Having these beautiful pieces in the collection challenges, enlarges, and enriches the notion of American art.

The story continues in the Wehling Gallery and in Main

Gallery: more interesting art, more good curating, though none of the new works

has the same emotional power for me as the Saar woodcut, or the wit and

freshness of the Hagelberg, or the strangeness of the Raj batiks or the Dayak

shields. There is additional religious art, beautifully textured collagraph

prints depicting significant archeological sites in Palestine by evangelical

Christian printmaker Sandra Bowden, from her Israelite Tel Series, plus two

paintings by prominent Lutheran liturgical artist Ernst Schwidder. There are

new acquisitions by local and regional artists already well represented in the

collection: a highly stylized Indiana Dunes painting by Vin Hannell, a pencil

sketch and still life in oil by Indiana Dunes painter Frank Dudley, an oil

painting of a Venetian scene by Conrad Juestel, plus two works by his protégé,

the recently deceased Virginia Phillips. Those five new Junius Sloan

watercolors mentioned earlier adorn a single wall; the corresponding wall

across the gallery holds four Japanese Ukiyo-e prints.

The story continues in the Wehling Gallery and in Main

Gallery: more interesting art, more good curating, though none of the new works

has the same emotional power for me as the Saar woodcut, or the wit and

freshness of the Hagelberg, or the strangeness of the Raj batiks or the Dayak

shields. There is additional religious art, beautifully textured collagraph

prints depicting significant archeological sites in Palestine by evangelical

Christian printmaker Sandra Bowden, from her Israelite Tel Series, plus two

paintings by prominent Lutheran liturgical artist Ernst Schwidder. There are

new acquisitions by local and regional artists already well represented in the

collection: a highly stylized Indiana Dunes painting by Vin Hannell, a pencil

sketch and still life in oil by Indiana Dunes painter Frank Dudley, an oil

painting of a Venetian scene by Conrad Juestel, plus two works by his protégé,

the recently deceased Virginia Phillips. Those five new Junius Sloan

watercolors mentioned earlier adorn a single wall; the corresponding wall

across the gallery holds four Japanese Ukiyo-e prints.

Returning to the West Gallery, I cannot make strongly enough the point that is so obvious to me here: the permanent collection of the Brauer Museum of Art is becoming, as America itself is becoming, more richly multicultural, more broadly international, more deeply interreligious and interdenominational. While all of the artists with works in the Sloan Gallery (except O’Keeffe) were white males, and all (except Audubon) were American-born and of northern European Protestant descent, I am pleased that the new acquisitions include, by my count, works of art by six women. In addition to those already mentioned, new works have come from Jewish American photographer Louise Witkin Berg. These acquisitions, all gifts, seem so wise and generous to me, and reflect so positively on the university entrusted with their care, whose values they body forth, as that university imagines itself at its very best.

John Ruff is professor of English at Valparaiso University.