Three years ago my passengers were in the Congo hiding from war’s crossfire. Now they are in my Prius on slippery Wisconsin roads, maybe not fearing for their lives, but certainly wondering, “How did we get here? And who is this guy driving the car?”

I have some time to think as I drive my passengers from Appleton to Oshkosh. The Weather Service calls the freezing rain and sleet coming down a “wintry mix,” so the windshield wipers are on. Conversation in the car is difficult. I don’t hear well, especially when there is a lot of background noise. The other passengers in my car are fluent in six languages, but not English. We do a lot of smiling and pointing, but after a while it’s just easier to travel in silence.

I met Jonas and his wife and daughter

just twenty minutes ago, right after I arrived at their house. Pastor John

introduced us in their living room before heading out to his van to shuttle a

different refugee family to the worship service we are all about to attend.

Sophie, the daughter, has good English, but she’s a teenager. She spends most

of the drive texting her friends.

I met Jonas and his wife and daughter

just twenty minutes ago, right after I arrived at their house. Pastor John

introduced us in their living room before heading out to his van to shuttle a

different refugee family to the worship service we are all about to attend.

Sophie, the daughter, has good English, but she’s a teenager. She spends most

of the drive texting her friends.

Jonas points to the clock on the dashboard. “Clock,” I say, then point to my watch. I point to the speedometer, then change it to kilometers per hour, because he is probably more familiar with kilometers. We’re traveling over 100, which feels unsafe on these roads, so I switch back to miles per hour. He is watching the animated display that records how much fuel we’re using and whether the Prius is running on gas or electricity. I have no idea how to say “fuel economy” in Swahili. The only word I know is “Papá,” which I overheard Sophie call Jonas. “Papá,” I repeat. “Hey, I just learned my first word is Swahili!” I beam. Jonas, Sophie, and her mother beam back.

I ask Jonas if he can drive. Sophie laughs. Jonas smiles and shakes his head, no. I realize that probably the family did not have a car back home. So the transportation barrier in getting the family to church is more than just getting the family a reliable car. Someone in the family will need to learn to drive. In a foreign country. Where the road signs are in an unfamiliar language.

During the twenty minutes of silence in the car I think about what it would be like to be a refugee. Most of the refugees from central Africa who have settled in our part of Wisconsin have fled tribal wars. Some have lived in multiple countries, picking up new languages on the way. In Oshkosh we do not call it “English as a Second Language” anymore. It’s “English as a Foreign Language.” It’s humbling to me. I took French for eight years, but have never had occasion to speak it. I took Biblical Greek and Hebrew in seminary, but all I can do in those languages is sound words out and look them up in my dusty lexicons.

I wonder what it would be like to have to leave my home with only the things I could carry. What would I take with me? Reflexively I think about my baseball card collection. I’ve been paring it down the last few years, so I only have around 4,500 now. I ask myself, “If I could only bring one baseball card with me, in my wallet, which one would it be?”

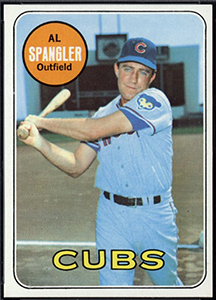

“Al Spangler,” is my immediate, surprising answer. I have a card that is more than 100 years old. I have cards of Hall of Famers and All Stars. I have cards that mark important, historic milestones. This is not one of them. Al Spangler was a part-time outfielder, never a star.

I remember getting his card on a rainy Sunday afternoon. It was 1969. My brother, age 8 at the time, and I, 5, put on our slickers and walked a few blocks to Walgreens in the East Bluff neighborhood of Peoria, Illinois, our hometown. A pack of cards cost a nickel then. I recognized the Cub uniform Spangler was wearing. He had a grin on his face, posing for the photograph of his follow-through of a swing of his bat. The Cub logo on his sleeve smiled, too. Despite his benchwarmer status, he would hit four home runs for the Cubs that year. The team finished in second place, behind the World Series champion New York Mets.

I want to ask my new friends, “What’s your Al Spangler? Do you have one possession that connects you to home?”

We get to worship a little late, I think. It’s not clear to me when worship actually started. The choir, which I’m told is usually accompanied by a synthesizer, sings a cappella. Someone explains to me that the instrument or its owner—maybe both—have gone to North Dakota. No one knows why.

There are two other white people. It appears that one understands Swahili, the language we’re worshiping in. I only grasp the occasional “alleluia!” and “amen.”

Pastor Shadrach introduces the guests. I am surprised when the three men sitting in front of me stand. I had assumed that all the Africans were part of the fellowship. When Pastor Shadrach introduces me, I stand and smile a lot. I thank him for getting the choir to participate in the Interfaith Festival of Gratitude the week before. They had sung two songs in a call-and-response style that filled the city’s Grand Opera House with joy.

The guest preacher begins his sermon in English. “I could preach in Kiswahili!” he begins. “I could preach in ____!” He completes that sentence six different ways before settling on English. Pastor Shadrach, at his side, translates into Kiswahili. But sometimes the preacher switches to Kiswahili and forces Pastor Shadrach into English. The preacher is passionate and animated. I miss a lot, but he’s repetitive enough that I get his message: Trust Jesus; He is so good.

After the service, I ask numerous people what Jonas’s wife’s name is. Maybe Pastor John gave her name during introductions and I didn’t catch it. Maybe he didn’t say her name at all. I want to be a good host for our return to Appleton, but trying to find out her name is like a frustration dream. I ask Pastor Shadrach, “What’s Mrs. Jonas’s name?” He points her out, thinking I’m in a hurry to get on the road and cannot find her. Finally, I ask Pastor John, who doesn’t know. Then he tells me, “It would be impolite to call her by first name. I just call women of her age from the Congo ‘Madame.’”

In that shining moment, I am able to address about one third of the worshipers by name! I spot Jonas and Sophie at the door, waiting for me. “Jonas, Sophie, let’s be on our way. Madame, take my arm because it’s slippery and your shoes are smooth on the bottom.” We smile at each other and head to the car.

When I pull into the driveway, Jonas turns to me and says, “Thank you! You have us so happy! So happy!”

“Yes, Jonas, I am happy. I have made new friends today!”

Sophie walks beside Madame up the icy path to the door.

On the drive home I wonder what it would be like to get into a car with a stranger in a strange country, knowing only, “This is Pastor Tom. He will drive you to church.” I am humbled that they put such trust in me. I realize that I too, am so happy.

The Reverend Doctor Thomas C. Willadsen is pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Oshkosh, Wisconsin.