Two old artist friends from Seattle have paintings hanging just around the corner from each other in the West Gallery at Valparaiso University’s Brauer Museum: a mostly abstract, partially figurative painting by Kenneth Callahan, Fossil Canyon, and an abstract expressionist painting by Takuichi Fujii. Callahan’s place in the history of American art, as a founding member of the Northwest School, as one of the Northwest Mystics who were important precursors for abstract expressionism, is well established. Fujii, though once a member of Callahan’s circle in Seattle, was until quite recently largely forgotten and virtually unrepresented in American museums (the Brauer owns one piece, the Wing Luke Museum in Seattle another). Now, after having dropped out of sight and faded from memory since the 1940s, Takuichi Fujii has been rediscovered and his importance is at long last being reassessed.

The Brauer’s Fujii, a calligraphic abstraction painted with broad, bold brushstrokes in black enamel on an unstretched canvas, occupies a place of honor in the exhibit, front and center on the wall between a lovely Joan Mitchell and a recently acquired Al Held. The Callahan painting and Elaine de Kooning’s Veronica face each other across the gallery and function as boldly colorful bookends. Fujii, given pride of place, might have achieved artistic greatness and acclaim on a par with other painters featured in the exhibit but for circumstances of history and race which contributed to his almost being forgotten.

I say “almost.” The Brauer’s Fujii is a recent gift from Japanese print expert Sandy Kita, Fujii’s grandson, and his wife, Terry Kita, longtime friends of the Brauer Museum. Sandy Kita has been instrumental in assessing, expanding, and improving the Brauer’s collection of Japanese prints. He helped to curate a major Brauer exhibition of esteemed printmaker Sadeo Watanabe (whose image Ten Virgins graced the cover of the Lent issue of the Cresset this year), and brought to the Brauer an exhibition by contemporary Korean abstract artist Sue Kwok. Together, the Kitas have helped facilitate the rediscovery of Takuichi Fujii.

Sandy Kita (whom I met years ago through my wife, Gloria Ruff, the Brauer’s associate curator), gave me a bound photocopy of his grandfather’s art diary, entitled Minidoka XX, not long after he and the late Reverend Honda Shojo finished translating and annotating it in 2011. I have been reading it, teaching it, and writing about it since then. In Kita’s introduction to that version of the diary, he relates how in 1999 he found a cache of his grandfather’s art in a box in the back of his mother’s closet while cleaning out her apartment in Chicago after she died. Fujii himself had died in 1964. I assume the Brauer’s Fujii came out of that cache, which included around 100 works, oil paintings, water colors, a pair of carved wooden sculptures of Fujii and his wife, and, most significantly, an art diary Fujii kept during his family’s incarceration during World War II. Historian Roger Daniels, an esteemed expert on American immigration and on the Japanese internment, calls Fujii’s art diary the most remarkable document by a Japanese prisoner to come out of the camps. Given the vast amount of materials that have been recovered from ten different camps over the past seven decades, that is saying something. Though I’m not sure his claim goes far enough: in as much as the diary is a work of composite narrative art, both words and images, in Japanese, in English, and sometimes in Japlish, it is so much more than a document, with expressive means capable of great power, nuance, and depth.

Daniels penned the foreward to The Hope of Another Spring: Takuichi Fujii, Artist and Wartime Witness (University of Washington Press, 2017), a new book from Seattle-based art historian Barbara Johns. Having already written three excellent books about Seattle Issei (first generation) artists, no art historian alive could have been better prepared than Johns to write Fujii’s story. This began the heavy lifting involved in re-establishing Fujii’s reputation as a significant West Coast artist. (Johns also curated Witness to Wartime: The Painted Diary of Takuichi Fujii, a traveling exhibit that so far has appeared in Boise, Idaho; Tacoma, Washington; and Alexandria, Louisiana.)

In her book, Johns situates Fujii in a number of significant overlapping contexts. She weaves his biography into the larger history of Japanese immigration to the United States from the late nineteenth century to its curtailment in 1924. She provides local history that shows what made Seattle’s Japanese immigrant community distinctive, and against that background she inserts Fujii into an artistic milieu in which he came to thrive, composed of both Japanese and Caucasian artists, some of them highly accomplished. Johns provides a fascinating and inspiring account of Fujii’s participation with other Seattle-based Japanese immigrant artists in an art circle gathered by Kenneth Callahan. It seems the Seattle art scene in the 1930s largely revolved around Callahan, who recognized something distinctive in the line and color used by the Japanese urban scene painters he welcomed into his circle. It is hard to imagine Fujii flourishing as he did during the 1930s apart from those Japanese friends and without Callahan. Daniels claims that group of artists who socialized in Callahan’s home and exhibited together, the Group of Twelve as it came to be called, may have been the only interracial group of artists then working together in America, or one of very few. Mark Tobey, the fourth member of the Northwest Mystics and considered the founder of the Northwest School, acquired his interest in Chinese calligraphy while in Seattle. Given Jackson Pollock’s documented interest in Mark Tobey’s art, it’s hard to deny a strong West Coast influence on abstract expressionism, with a particularly Asian accent we can see clear as day in the Brauer’s Fujii.

Johns’ chapter on Fujii’s life in Chicago after the internment breaks new ground for me; I learned Chicago became the largest population center for Japanese Americans after the war. For people back in Seattle, Fujii fell off the map after the camps closed and the war ended. Some thought he had died. Others believed he had returned to Japan. The Brauer’s Fujii dates from his time in Chicago, during which time Fujii’s abiding interest in abstraction, which first appeared in his art diary, came to fruition.

The art diary is the single most important work of Fujii’s to come to light, and Johns provides a rich context for it, reproducing a sizable portion of it in her book. She includes commentary and captions Fujii wrote for almost every facing page. She has also included color reproductions of a selection of paintings that seem to have begun as drawings in the diary, as well as paintings from the 1930s. Johns’ scholarship is thorough and carefully annotated, and her analysis of the artwork excellent and readable. Johns maintains that the experience of confinement is ever-present in Fujii’s diary. I read the diary somewhat differently. Even at the euphemistically named “Camp Harmony”—a temporary detention center hastily thrown together at the Western Washington State Fair Grounds in Puyallup, Washington, where the Japanese residents of Seattle were locked up amidst armed military guards, watch towers, and barbed wire fences—I also see something else begin to appear. Exactly thirty-eight pages into the diary, after we have seen Fujii and his family taken away in buses, seen them locked up in converted cattle stalls, seen the guards, the fences, the squalid shower room, and the men’s latrine, we see—quite inexplicably—teenagers playing volleyball. In the next image we see a crowd watching dancers perform onstage, and, in the next, a crowd gathering to watch a sumo wrestling match. In such scenes, the fences, guards, and watch towers almost disappear, or they disappear entirely. This is not to discount or deny any of what Johns sees—there is a pervasive feeling of sadness, lassitude, and degradation at Puyallup to go with the sense of confinement she feels is so dominant. But I also see a man who, through the practice of his art, begins to enact and record a process through which he starts to draw himself to a different place, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. At Minidoka, at its worst, it is not so much a sense of confinement I feel looking at Fujii’s images as a sense of abandonment. At its best—or at Fujii’s best—I see him recording, through frequent images of himself at leisure or working at his art, his effort to escape or transcend the worst aspects of a terrible ordeal. He records that ordeal faithfully, and through that process achieves a sense of purpose, psychic health, and wholeness despite circumstances that tragically interrupted his career and nearly ruined his life.

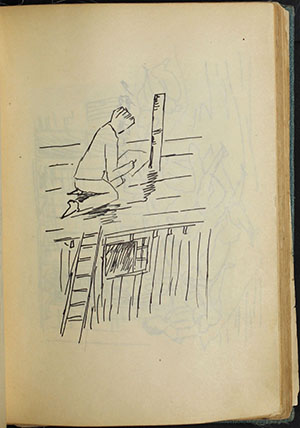

I especially love an image he drew of himself drawing up on the roof of the barracks. For me, this image connects to the concluding sentence of the only Artist Statement we have from Fujii, written for an exhibition before the war and reprinted as an appendix to Johns’ book:

To me, the most important element in painting is its power to raise the observer above the everyday affairs of life into a higher plane of existence.

In his image of himself drawing up on the roof, a ladder leaning up against the barracks becomes a crucial metaphor for Fujii’s art and his project in the diary: to provide witness to a grave injustice that caused terrible suffering and trauma, and also to record how he and his community strive to live their lives with dignity and purpose—sometimes with success. Most importantly, he demonstrates how through the practice of one’s art one can survive, surmount, and even transcend awful circumstances and achieve a form of healing, all the while expressing essentials truths about that experience, about the human condition generally, and about the human spirit. This process of abstraction that Fujii practices has a spiritual dimension beyond the aesthetic that both interests and inspires me.

Sandy Kita’s

introduction to his grandfather’s diary at the end of Johns’ book is crucial

for the way it gives us both the man and the artist, for how it puts Fujii in

his studio again, and at his breakfast table on Saturday mornings presiding

over the conversation. For Kita, Fujii was the man who helped to raise him after

the early death of his father, and also the man who gave him his first art

lessons. Kita’s account shows us his grandfather still pursing his art, still

embracing and expressing his Japanese culture as well as the culture around

him. Under his grandfather’s influence, Sandy Kita would grow up to study art

at the University of Chicago, earn a Ph.D., and become an expert in Japanese

Ukiyo-e prints. Perhaps no one alive is better prepared to put Fujii’s art

diary, an e-nikki, in traditions of Japanese art and Japanese art

diaries, and I believe Kita does it very well.

The abstract expressionist painting by Fujii that the Kitas donated to the Brauer shows the full flourishing of an impulse toward abstraction that was planted in Seattle, was born in the camps, and was likely guided by new non-representational modes of art that Fujii encountered in Chicago. As he practiced this new mode of painting, we can imagine him drawing upon training he received in Sumi (black ink wash) painting while still a boy in Japan. We observe him drawing upon his skills in calligraphy as he did in the camps, but for new expressive purposes and with a very broad brush. I love Sandy Kita’s account of how his grandfather replaced his horse-hair brush with one he made himself, using his wife Fusano’s hair for its greater expressiveness. There is something very poetic in that gesture that I won’t soon forget.

If you can, visit the Brauer and enjoy the works by these two friends who are reunited in this exhibit. We could all learn something from Kenneth Callahan and the other Seattle artists who welcomed Fujii and other Japanese immigrant artists into their circle. It’s a rare treat, a Brauer exclusive, to see works by Callahan and Fujii hanging together again after all these years, the Fujii so bold and sure in it gestures, the Callahan still searching, still on the road in that deep canyon, but the colors so rich, so warm, and so welcoming.

John Ruff is professor of English at Valparaiso University.