I recently taught an honors college seminar that included on the syllabus an exploration of the topic of forgiveness. All of the students in the seminar were professed Christians, though they did of course differ from one another in terms of denominational affiliation and theological literacy. Even so, they seemed to agree with one another completely about certain basic features of forgiveness. Whatever it was, they all said, it had to be offered unconditionally and unilaterally to those who had wrongly offended or otherwise injured them. It did not matter whether the offender was repentant or contrite. Nor did it even matter whether the offender knew that he or she had been forgiven by the victim. Forgiveness, whatever it was exactly, was something undertaken primarily, sometimes exclusively, for the sake of the forgiver. Forgiveness relieved the offended party from feelings of revenge or resentment so that he or she could “move on.”

This apparent unanimity of opinion quickly crumbled in view of the assigned readings and in response to interrogation. If we are to forgive as Christ forgives us and because Christ forgives us, should we conclude that Christ forgives us primarily for his sake rather than for ours? Would we actually be forgiven if we had no knowledge that we had been? If we inform someone that we have forgiven them for something that they did not and still do not regard as wrongful, would they be right to think us presumptuous and offensive? Are people who wrongly injure us and repent of it to be treated in the same way as people who wrongly injure us and feel no regret or remorse for doing what they did? When the psalmist asks God to “wash away my sin; make my guilt disappear,” does this not suggest that forgiveness has something to do with the removal of the offender’s subjective and/or objective guilt? If so, does this not presume that offenders must be informed that they have been forgiven by their victims? As often happens in seminars, the students quickly came to doubt whether they really thought what they initially claimed they had thought.

In order to make these questions and perplexities clearer, we read together with some care a philosophical treatment of forgiveness written by someone whose own perspective on the matter was avowedly secular. By comparison to my students’ Christian view of forgiveness, the secular philosopher’s view seemed remarkably stringent and demanding, so much so that many students were initially quite troubled by it. The author of the book, Charles L. Griswold, describes at considerable length a picture of what he calls “perfect forgiveness.” In other words, he establishes an ideal that he believes we should all strive to approximate, even though we cannot always meet all of the conditions he describes as being essential to “perfect forgiveness.”

For Griswold, unlike the students, forgiveness must be a morally transformative social transaction between two people, the offender and the victim. In other words, forgiveness should change for the better both the offender who inflicted an unjust injury and the victim who feels resentment toward the offender and who may harbor thoughts of revenge. “Perfect forgiveness” cannot be unilateral or unconditional. Moreover, the larger goal of forgiveness is relieving the offender’s guilt rather than diminishing the victim’s resentment. Griswold develops this picture of perfect forgiveness in considerable detail. He first lists six conditions that the offender must meet in order to qualify for forgiveness and he then outlines six parts of forgiveness that the victim must complete.

In order to qualify for or merit forgiveness, offenders must 1) take responsibility for what they did by acknowledging performance of the injurious actions; 2) repudiate those injuries by acknowledging that they were wrong; 3) express regret over the wrongdoing; and 4) commit in word and deed to becoming the sort of persons who would not in the future inflict similar unjust injuries upon others. Taken together, these four conditions that the offender must meet are called “contrition.” But there remain two additional conditions: 5) offenders need to show that they understand, from the victims’ point of view, the damage caused by the injury, and 6) finally, offenders must offer their victims an account of how they came to do what they did.

Once offenders have met all of these conditions (and remember that Griswold is describing “perfect forgiveness” here), the victims must 1) forswear revenge, promising to undertake no personal retributive action (note that this does not mean that victims must refrain from cooperating with the state in order to achieve justice in a courtroom); 2) reduce feelings of resentment; 3) commit to gradual elimination of resentment altogether; 4) refuse to reduce the offenders to their actions, i.e. refuse to consider the offenders “bad people”; 5) drop all feelings of moral superiority and recognize instead the shared humanity of offenders and victims; and 6) address the offenders to inform them that forgiveness has been granted.

Most Christians would agree with Griswold’s fine description of what forgiveness means for the victimized party, for the forgiver—except for the requirement that the victim must inform the offender that forgiveness has been granted. Bishop Desmond Tutu, for example, in a book that he wrote about forgiveness with his daughter Mpho, outlines a “fourfold path” to forgiveness that is in many ways identical to Griswold’s description of what the victim must do in order to forgive (after forgiveness, the victim becomes a “hero” in Tutu’s view). However, Tutu is quite clear that forgiveness is not something we do on behalf of the offender; we do it on behalf of ourselves. “When we forgive, we take back control of our own fate and our feelings. We become our own liberators. We don’t forgive to help the other person. We forgive for ourselves. Forgiveness, in other words, is the best form of self-interest. This is true both spiritually and scientifically.”

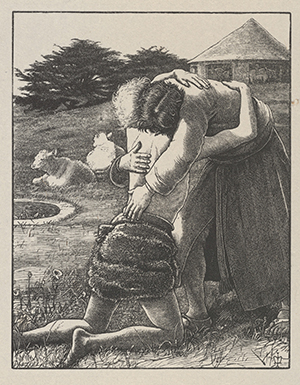

Tutu is but one of many outstanding Christian theologians, philosophers, and pastors who argue that forgiveness is for the sake of the forgiver and that it is unilateral and unconditional. For example, the distinguished Catholic philosopher Eleonore Stump, following Aquinas, argues against what she takes to be the “common view” among writers like Griswold on forgiveness, which makes forgiveness contingent upon repentance and reparation on the part of the offender. On the contrary, since forgiveness is an expression of Christian love, which desires both the good of the other and union with him, it must be offered without conditions and out of a desire for reconciliation. The parable of the prodigal son provides the decisive image of forgiveness on this account. My students, it turns out, had ample support for their initial views of forgiveness. Christians would seem to be almost uniformly opposed to the conditional character of forgiveness as Griswold understands it. Tutu’s “fourfold path” to forgiveness never depends upon anything the offender does or does not do until the victim decides at the end of the process whether to renew or to release the relationship between him or herself and the offender. Renewal depends at least to some degree upon the willingness of the offender to begin a new relationship.

II

This apparent unanimity of theological opinion about the nature of forgiveness may not be what it first seems, however. Consider Tutu’s example. Only seven pages after he has stated quite categorically that we do not forgive to help the other person, he says, “Forgiveness is the grace by which we enable another person to get up, and get up with dignity, to begin anew.” Later in his book, Tutu considers pertinent biblical examples of forgiveness. He writes, “In the Christian tradition, we often recall the story of the repentant criminal who was crucified beside Jesus. He was a man who had committed crimes punishable by death. Jesus promised him that, because of his repentance, ‘this day we will see one another in paradise.’ He was forgiven.” We would seem to have here an authoritative example of forgiveness, cited approvingly by Tutu, in which the forgiveness was given in response to repentance and was openly pronounced to the offender.

Some notable Lutheran theologians have taken the story of Christ’s forgiving the repentant thief on the cross as normative both for the Church and for the individual Christian. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, for example, in his much-quoted opening to The Cost of Discipleship, critiques unconditional forgiveness dispensed by the Church as being at the very heart of what he means by cheap grace. “Cheap grace is the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, Communion without confession, absolution without personal confession.” However, like other Lutheran theologians and perhaps most Christian theologians, Bonhoeffer can be quoted against himself. He too was of a divided mind, so he can write at times as though forgiveness is unconditional and at other times as though it is most definitely not unconditional.

In addition to the equivocations already noted, Christians have, I think, at least three additional good reasons to wonder about notions of forgiveness as unconditional and unilateral. First, the patterns of routine forgiveness in everyday life among religious and non-religious people alike are seldom unconditional and unilateral. Tutu discusses these daily family dramas at length. A typical scene involves a child carelessly breaking a vase, admitting it, weeping over it, feeling ashamed, promising to make amends and to never do such a thing again, etc. In return, the parent admits distress but quickly offers forgiveness to the child who gladly accepts it even though the child may be asked to make some kind of restitution. So our first sense that forgiveness is to some degree conditional arises from our common experience.

Second, Christians are formed by the liturgy. And Sunday services do not begin with an announcement of God’s forgiveness of all of our sins in order for God to feel good about Himself and to liberate Him from enslavement to the anger and resentment he feels toward us. Instead, our Lutheran services begin with our acknowledgement of our sins, our repentance for them, our resolve to do better, and our beseeching God for forgiveness. Then, “in the stead and by the command of our Lord Jesus Christ,” the pastor forgives us all our sins. We might well view this weekly ritual as the liturgical expression of what Bonhoeffer means by “costly grace.” Whatever may be the case theologically, liturgically we are habituated to think that forgiveness comes to us from a loving God in response to our contrition and repentance. Should we not then think that our forgiveness of others should depend to some extent upon their acknowledgement of wrong-doing and their remorse over it?

Third, finally, and perhaps most importantly, Scripture seems to suggest more often than not that forgiveness is as much for the benefit of the sinner as for the benefit of the one offering forgiveness, whether the one offering is God or another human being. A whole genre of the Psalms, the penitential psalms, is filled with cries of repentance and pleas for the relief of guilt through forgiveness. Should we not therefore think of forgiving our brother or sister as at least in part an effort to relieve him or her from guilt? Though the biblical record is mixed, as it so often is, on the character of Jesus’s forgiveness of our sins, we have already noted that some of the most memorable stories of forgiveness seem to portray it as a response to repentance. Moreover, Jesus confers upon the disciples and by implication the church the power to forgive or to retain sins. Again, if forgiveness is unconditional, on what possible basis could the church retain sins? According to the “Office of the Keys,” the church should forgive the sins of the penitent and retain the sins of the impenitent.

III

Though everyday life, liturgical practice, and the biblical record do challenge standard assumptions among Christians about forgiveness, there may be ways to retain most of these assumptions even as Christians acknowledge the force of the challenges. Christians might, for example, distinguish between forgiveness and reconciliation. As Tutu notes, forgiveness may lead to reconciliation or renewal of relationship, but it need not do so. So we might say that though forgiveness is unilateral and unconditional, reconciliation is mutual and conditional. Indeed, genuine reconciliation with someone who has wronged us may well include, on the wrongdoer’s part, some of the very “conditions” that Griswold lists as qualifications for forgiveness. Indeed, perhaps Griswold has things backwards. Forgiveness, at least for Christians, comes first, unconditionally, and may lead to the offender’s acknowledgement of wrongdoing, remorse for it, resolution to refrain from such wrong actions in the future, and empathy for the victim’s suffering. And these actions may in turn lead to reconciliation with the injured party who has forgiven the wrongdoer. Though the idea of reconciliation as distinct from forgiveness may help to resolve some of the difficulties about forgiveness, it does presume that the victim must declare forgiveness to the offender if there is to be any chance of reconciliation.

A second way of resolving some of the difficulties we have considered may be to recall another famous scene in Scripture, the moment when Jesus prays, “Father forgive them, for they know not what they do.” Notice that Jesus does not forgive those who crucified him directly; he prays that the Father should do so. So we might say, remembering that only God finally has the power to forgive sins directly or indirectly through those acting in God’s stead, that we should ask God to unilaterally and unconditionally forgive those who have injured us even though we may well require that some conditions be met before we forgive them. Thus, we can find a way to be unconditional and conditional at the same time: unconditional in our prayer, conditional in our forgiving relation with those who have offended us.

A third way of resolving the problem of the unconditional character of forgiveness turns the second strategy on its head. Instead of construing God’s forgiveness as unconditional while our forgiveness of others remains conditional, we might argue, following Bonhoeffer and others, that God’s grace is costly in order that ours may be cheap for our neighbors. Because we are forgiven, repentant sinners, we can and should be forgiving, i.e. willing and ready to forgive those who have wronged us without requiring of them what God requires of us. These two diametrically opposite strategies do not so much present us with a choice as they raise a fundamental question. To what extent should our practices of forgiveness mirror exactly God’s forgiveness of us? To what extent should we strive to imitate in everyday life with our neighbors, the Church’s practices of forgiveness, as the Church acts in God’s stead?

Fourth and finally, Christians might resolve many of the issues surrounding the concept of forgiveness by re-conceptualizing the whole matter as one of character rather than individual acts. Instead of asking what exactly an act of forgiveness entails, ask what the virtue of forgivingness involves. Such a virtue would be part of what it means to be “Christ-like,” and it might be subsumed as a smaller virtue under the larger virtue of charity. Forgivingness would involve the disposition to forswear revenge and resentment and to seek instead a restored relationship. However, like all the other Christian virtues, charity and forgivingness would be governed by Christian practical wisdom, the virtue that would enable Christians to forgive in the right way at the right time for the right reasons. The path to forgiving well would not be laid out in advance. Instead, forgiveness may or may not include or require repentance and contrition in a particular case. The overall intention would be to forgive in all cases; however, forgiving well in any particular case would involve doing what good forgiveness requires in that case. Under this re-description, forgiveness is a specific kind of charitable exercise, subject to a wide variety of contextual considerations, but seeking, as love always seeks, the good of the other and union with that other in at least a common humanity.

IV

Why should Christians trouble themselves to examine their standard assumptions about forgiveness being unilateral, unconditional, and private, i.e. not even shared with the offender? After all, if forgiveness is done simply for the sake of the one doing the forgiving, as Tutu sometimes argues and as most Christians think, it should be much easier to persuade Christians to forgive others than it would be if forgiveness were primarily for the sake of others, for those who have offended. This is, as they say, human nature. There can be no question that forgiveness is good for the forgiver, psychologically, spiritually, even physically. Bishop Tutu references and summarizes the immense amount of social-scientific research that documents this fact. And this research in turn informs an avalanche of popular culture treatments of forgiveness as being both good and good for you. As recently as May 19, 2019, for example, Tim Herrera wrote a piece for the New York Times entitled “Let Go of Your Grudges! They’re Doing You No Good.” During the course of his column, he cited the huge Stanford Forgiveness Project, which has conclusively shown that forgiveness reduces stress, reduces anger (as it should), improves the health of your heart, and just generally enhances your physical and psychological well-being.

“Great news!” Christians may say. And up to a point, they should. Christians should certainly not be sorry about the discovery that forgiveness is good for the body as well as the soul. They should probably stop short of rejoicing over what they take to be the discovery that Jesus was, in addition to being the Son of God, an excellent psychotherapist before his time. In other words, Christians should wonder about whether their primary motive to forgive should be improvement of their own cardiac health. What about the offender and the burden of guilt he or she carries? Should concern about this and for the offender’s overall wellbeing have no place in a Christian’s motive to forgive? Something can be at one and the same time good for others and good for oneself. The question is where the Christian should put the emphasis. Is forgiveness primarily a spiritual practice or a form of therapy? Tutu reminds us that forgiveness is by no means an exclusively religious practice, and for secular people forgiveness therefore may well be an exclusively private matter of self-therapy. But for Christians, forgiveness is a religious practice, so that even though it may improve their health, they should, I think, worry over whether that should be the main or the only reason they forgive their brothers and sisters.

What practical difference does this all make for Christians? I think that, apart from matters of motivation, forgiveness for Christians must entail announcing forgiveness to the offender if this is possible. Of course in those cases that most arise in psychotherapeutic situations, the offender or offenders (often parents) cannot be told they are forgiven, because they are deceased. So in these cases, we do the best that we can in prayer, in the healing of memory, and in sharing the news with other family members. But these cases, emotionally powerful as they may be, should not tempt us to think that in the vast majority of cases where it is possible to let those who have wrongly injured us know that they have been forgiven by us and by God, we may choose whether or not to do so. Indeed, I would argue that we must do so.

In sum, Christians should think hard about forgiveness for many reasons. First, its practice is close to the heart of the Christian gospel. Second, since forgiveness is both a secular and a religious practice, it is all too easy to lose sight of those aspects of the practice that are distinctively Christian. Third and finally, what we think about forgiveness informs the motive, the manner, and the substance of our practice. Thought of a certain kind leads to action of a certain kind. Of course, for Christians, it is the Lord who finally enables us to forgive. And though we may not be able to be certain of many things involving forgiveness, of one thing we can be sure. The Lord did not forgive us for His sake, but for ours.

Mark R. Schwehn is professor of humanities in Christ College, the Honors College of Valparaiso University, where he served as dean from 1990-2003. He is the founding project director of the Lilly Fellows Program.

Works Cited

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. The Cost of Discipleship, trans. R.H. Fuller. London: SCM Press, 2001: 4.

Griswold, Charles L. Forgiveness: A Philosophical Exploration. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007: 49-58.

Herrera, Tim. “Let Go of Your Grudges! They’re Doing You No Good.” New York Times (May 19, 2019).

Stump, Eleonore. Atonement. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018: 80-83.

Tutu, Desmond and Mpho Tutu. The Book of Forgiving. New York: HarperCollins, 2015: 16, 23, 56, all italics mine.